Natural language models and strategic command systems

All philosophy is a critique of language - Wittgenstein

Strategy Instructions

The components of strategy instructions are: conditions (signals) and actions. The core idea of strategy is “condition => action”. Set any condition, and once it is met, trigger the trading action.

Common conditions include: price, assets, and time. Common actions include: buying and selling. With just these few elements, very rich trading strategies can be constructed. Whether good trigger conditions can be found, whether good actions can be taken under established conditions, and whether this process can continue to cycle and continue to profit - this is the embodiment of trading will in a quantified system. When people talk about quantification, they usually think of strategy first. It is the soul of the quantification system.

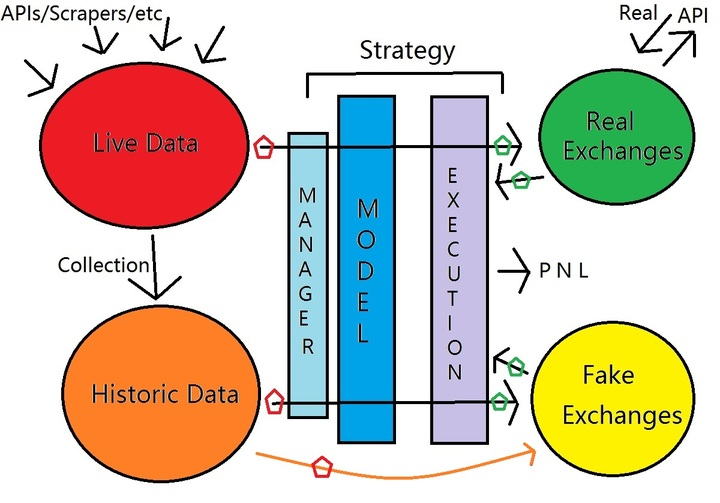

A basic prototype of a quant trading system should include:

- Strategy system

- Trading system

- Intelligence system

- Real-time data

- Historical data

The intelligence system includes trading data, factor data crawling, interface acquisition, and various alternative data factors, together forming the system’s data pool. From the perspective of Python, the data acquisition interface simply includes the following types.

Relationship between Data and Instructions

After obtaining the data and initial factor metadata in the previous step, they are usually highly structured and cannot be directly used for strategies. Functions and models for filtering, searching, aggregation, statistics, and other data processing exist, which have clear input, processing logic, and output. The corresponding relationships between these clear, specialized processing instructions and natural language are relatively simple and fixed.

For example:

1 |

|

And similar expressions such as “get the sum of d0 to d3”, “sum up d0 to d3”, and “add d0 to d3” all have high semantic similarity. Therefore, the difficulty lies in the rules and generation of input and processing logic. The highest difficulty lies in the correspondence between natural language models and mathematical expressions, as well as logical expressions (which can be understood as pseudocode with fixed rules and templates). It is extremely difficult to generate and accumulate such data. Therefore, the design of this mathematical expression and logical expression system is the most fundamental and challenging work. On this basis, we need to introduce many concepts.

First-Order Logic

- George Boole

First-order logic (FOL), also known as first-order predicate calculus, allows for quantification of statements and is a formal system used in mathematics, philosophy, linguistics, and computer science. FOL is a mathematical logic that distinguishes itself from higher-order logic by not allowing quantification over properties. Properties are characteristics of an object; therefore, a red object would be described as having the property of being red.

The language of logical programs is a subset of FOL because it is useful for many tasks. FOL can be viewed as a language for logical programs that can add disjunctions and explicit quantification. FOL is first-order because it allows for quantification over individuals in a domain. FOL neither allows for predicates to be variables nor allows for quantification over predicates.

Second-order logic allows for quantification over first-order relations and predicates whose arguments are first-order relations. These are all second-order relations. For example, the second-order logic formula

defines symmetry for second-order relations, and if its argument is a symmetric relation, it is true. FOL is recursively enumerable, which means that there is a complete proof procedure in which every true statement can be proven using a proof program on a Turing machine. Second-order logic is not recursively enumerable, so there is no complete proof procedure that can be implemented on a Turing machine.

Propositional logic deals only with simple propositional statements, while FOL also includes assertions and quantification.

An assertion is like a function that returns true or false. Consider the following sentences: “Socrates is a philosopher” and “Plato is a philosopher”. In propositional logic, the two sentences are considered as two unrelated propositions, simply labeled as p and q. However, in FOL, the two sentences can be represented using assertions in a more similar way. The assertion is Phil(a), which means a is a philosopher. Therefore, if a represents Socrates, Phil(a) is the first proposition - p; if a represents Plato, Phil(a) is the second proposition - q. A key point of FOL can be seen here: the string “Phil” is a grammatical entity, and its semantics are assigned by assigning it to be true when a is a philosopher. The assignment of a semantics is called an interpretation.

FOL allows for the use of variables to infer properties shared by many components. For example, let Phil(a) represent a philosopher, and let Schol(a) represent a scholar. Then, the formula represents that if a is a philosopher, then a is a scholar. The symbol is used to mark a conditional statement. The left side is the hypothesis, and the right side is the conclusion. The truth value of this formula depends on the element labeled as a and the interpretation of “Phil” and “Schol”.

For each a, assertions of the form “if a is a philosopher, then a is a scholar” require the use of variables and quantification. Once again, let Phil(a) represent a philosopher, and let Schol(a) represent a scholar. The FOL statement

represents that regardless of what a represents, if a is a philosopher, then a is a scholar. The universal quantifier represents a claim for “all” choices of a, and the statement in parentheses is an idea that is true.

To demonstrate that the assertion “if it is a philosopher, then it is a scholar” is false, it can be shown that there are philosophers who are not scholars. This can be

expressed using existential quantification. For example:

- ¬(∀x)(Phil(x) → Schol(x))

- ¬(∀x)(Phil(x) ∧ ¬Schol(x))

The negation operator ¬ is true if and only if the statement is false; in other words, if and only if a is not a scholar.

The conjunction operator ∧ indicates that a is a philosopher and not a scholar.

Assertions Phil(a) and Schol(a) both have only one argument. However, FOL can also represent assertions with more than one argument. For example, “There exist people who can be fooled at any time” can be represented as

Here, Person(x) is interpreted as x is a person, Time(y) is interpreted as y is a period of time, and Canfool(x,y) is interpreted as person x can be fooled at time y. Clearly, the statement represents that at least one person can be fooled at any time, which is stronger than the statement “At any time, there exists at least one person who can be fooled.” The latter does not imply that the person being fooled is always the same.

The scope of quantification is determined by the set of objects that can be used to satisfy quantification (in some of the informal examples in this section, the scope of quantification is not specified). In addition to specifying the meaning of assertion symbols such as Person and Time, an interpretation must also specify a non-empty set called the domain, which serves as the scope of quantification. Therefore, a statement of the form in a specific interpretation is true if there exist objects in the domain that can be used to assign meanings to the symbols Phil and Schol.

Formation Rules

Formation rules define the terms and formulas of first-order logic, which can be used to write a formal grammar for terms and formulas, because they are represented as sequences of symbols. These rules are usually context-free (the result of the rule has only a single symbol on the left-hand side), unless infinite sequences of symbols are allowed and there are many starting symbols, such as variables in terms.

- Terms

Terms can be recursively defined according to the following rules:

- Variables. Every variable is a term.

- Functions. Every expression f(t1, …, tn) with n parameters, where each ti is a term and f is a function symbol with n parameters, is a term. In addition, constant symbols are function symbols with 0 parameters, and therefore they are also terms.

Only those expressions that can be obtained by applying the above rules a finite number of times are terms. For example, there are no terms containing predicate symbols.

- Formulas

Formulas (or well-formed formulas) can be recursively defined according to the following rules:

- Predicate Symbols. If P is an nary predicate symbol and t1, …, tn are terms, then P(t1, …, tn) is a formula.

- Equality. If the equality symbol is part of the logic and t1 and t2 are terms, then t1 = t2 is a formula.

- Negation. If φ is a formula, then ┐φ is a formula.

- Binary Connectives. If φ and ψ are formulas, then (φ ψ) is a formula. Other binary logical connectives can be defined similarly.

- Quantification. If φ is a formula and x is a variable, then and are formulas.

Only those expressions that can be obtained by applying the above rules a finite number of times are formulas. Formulas obtained from the first two rules are called atomic formulas.

For example,

is a formula, where f is a unary function symbol, P is a unary predicate symbol, and Q is a ternary predicate symbol. On the other hand, is not a formula, although it is a string of symbols from the vocabulary.

The parentheses in the definition are used to ensure that any formula can only be obtained by recursively defining it in a single way (in other words, each formula has a unique parse tree). This property is called the unique readability of formulas. There are many conventions regarding where to use parentheses in formulas. For example, some authors use colons or dots instead of parentheses, or change the position of the parentheses. However, every author’s definition must be shown to satisfy unique readability.

The rules for defining formulas cannot define the “if-then-else” function ite(c, a, b), where c is a condition represented by a formula, and ite(c, a, b) returns a if c is true and b if c is false. This is because both predicates and functions can only accept terms as their arguments, but the first argument of this function is a formula. Some languages built on top of first-order logic, such as SMT-LIB 2.0, allow such constructs.

SMT-LIB is an international initiative aimed at facilitating research and development in Satisfiability Modulo Theories (SMT). Since its inception in 2003, the initiative has pursued these aims by focusing on the following concrete goals.

- Provide standard rigorous descriptions of background theories used in SMT systems.

- Develop and promote common input and output languages for SMT solvers .

- Connect developers, researchers and users of SMT, and develop a community around it.

- Establish and make available to the research community a large library of benchmarks for SMT solvers.

- Collect and promote software tools useful to the SMT community.

This website provides access to the following main artifacts of the initiative.

- Documents describing the SMT-LIB input/output language for SMT solvers and its semantics;

- Specifications of background theories and logics;

- A large library of input problems, or benchmarks, written in the SMT-LIB language.

- Links to SMT solvers and related tools and utilities.

The Z3 engine is an efficient symbolic reasoning tool that was initially used for theorem proving and symbolic verification. However, its powerful features are now being applied in various fields.

To learn Z3, one first needs to understand how it does theorem proving (its original purpose), and then see how it can be applied to other fields.

In 1990, Halpern, J. Y. proposed two methods for solving probabilistic first-order logic. In 1998, Chiara Ghidini also proposed Distributed First Order Logic for use in distributed knowledge representation and reasoning systems (DKRS). In 2002, Anand Ranganathan Æ Roy H. Campbell used first-order logic for background-aware systems to represent information that cannot be quantified. In 2012, Fitting, M. applied first-order logic to automatic theorem proving.

With the help of the tools mentioned above, definitions, and formulas, we can say that as long as we have first-order logic, the results obtained, and the set of composite logics can convert structured (low degrees of freedom) natural language into corresponding data processing logic and executable strategies within a limited scope, which is no longer impossible to achieve.

Natural Language Modeling

In reality, a natural language model that can completely replace human communication and semantic parsing has not yet been developed. Therefore, it is unnecessary to pursue the ability to process relatively contextually dependent and complex languages. Through large-scale language corpus training, the model can achieve natural language semantic parsing and convert it into a set of first-order logic in a relatively structured (lower degree of freedom) natural language environment.

We often say “don’t speak incoherently, be coherent and cohesive,” meaning that the context of the vocabulary should have semantic coherence. Based on the coherence of natural language, the language model predicts the next word based on the previous words. If the parameters of the language model are correct and the word vectors of each word are set correctly, the language model’s predictions should be relatively accurate. With countless articles in the world, training data is endless. However, context dependency means that you cannot obtain enough information from just one sentence. So, what is this information?

For example, when we use a regular voice assistant to say “call my wife,” “call my mother,” “call my father,” the predicate “call(x)” is first parsed as an item (function). The term “wife,” “mother,” “father,” and so on are then parsed as items (variables). As previously mentioned, items and formulas are represented as a string of symbols, and these rules can be used to write a formal grammar for items and formulas. These rules are usually context-free. Otherwise, there will be an infinite number of symbols.

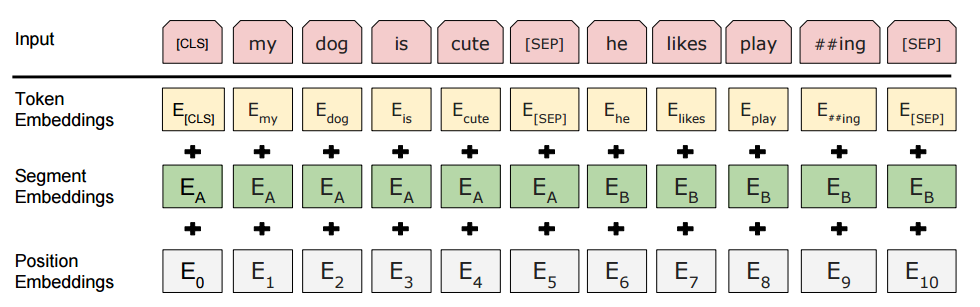

Therefore, we begin to compare symbols with existing symbols. For example, the function call() needs to know the phone number property of the input item, so it is reasonable to use “wife,” “mother” to refer to items in the symbol library. Thus, the matching is completed. The entire chain also works. We can also understand that if we use “Zhang San” or “Li Si” to refer to the item designated for dad, it will be impossible to complete the matching work without context (and there should be no context). This is the great difficulty of modern NLP compared to humans. Every normal person’s brain has a very large, fully trained context-dependent symbol system, and it is extremely difficult for a computer based on von Neumann architecture to have the same symbol system. This is also why modern language models like GPT-3 have already reached a parameter volume that home computers cannot handle. The larger the symbol system, the more connections between symbols, and the better the model’s performance. Therefore, after BERT, almost all models use pre-training. These pre-training models basically represent a basic symbol system. Based on this complete and massive symbol system, the learning difficulty and computational complexity of building larger symbol systems will be greatly reduced.

Therefore, once we have a clear understanding, we can find that by specifying the grammar rules on the input end and having a well-designed code (functions and symbol system) on the execution end, processing rule-based natural language into a string of executable functions is achievable.

So, HOW?

Translation Model OR Generation Model

We should be clear that the few-shot learning capability of GPT-3 is not universal. Although the model has impressed people with its learning of complex tasks and patterns, it can still fail. For example, even after seeing 10,000 examples, it cannot solve a simple task like reversing a string. It is essentially a network of nodes connected in a high-dimensional word embedding space. GPT-3 transforms the input words into high-dimensional space nodes in the network as a starting point and continuously searches for shortcuts to reach the next node, which is its perceptual world. In fact, it is only trying to understand the language dimension of humans and cannot understand the perceptual cognitive dimension of humans. This is the limitation of GPT-3 that cannot be broken no matter how much the model is expanded.

However, we should also know that our needs do not actually require the model to be intelligent to any extent.

From the conventional perspective, we have two seemingly feasible technical routes:

- NLP translation model

- NLU/NLG generation model

However, generally speaking, translation models have a higher probability of failure in grammar and logic after translation, and due to the much lower fault tolerance of first-order logic than natural language, the drawbacks of translation models in this task are obvious. For example, “I don’t want to eat apples.” and “I don’t eat apples.” The subtle semantic differences between these two sentences can be ignored in daily conversations, but from the perspective of logic, the semantic differences between “not,” “cannot,” and “do not want” are significant and require three separate functions to describe. The input and matching confusion in this process makes the requirement for humans very high after translation and the usability of the entire process very low.

Thus, we can understand that the core of the entire process becomes a dialogue system based on NLU, NLG, and an application layer composed of symbolic system sets. As we gradually clarify this technical solution, we can provide the following basic system structure:

Data Layer: Dialogue business data, open-source multi-turn dialogue data, etc.

Algorithm Layer: Syntactic analysis, fine-grained analysis, entity extraction, query error correction, etc.

Capability Layer: Natural Language Understanding, Dialogue Management, Dialogue Strategy, Strategy Optimization, Dialogue Factory

Application Layer: Real-time/historical data aggregation, statistics, analysis, visualization, backtesting, live trading

In the data layer and application layer, the financial data, factor library data, and the system’s own database are used as support.

New Chapter - GPT4

The publish of chatgpt is new phase of artificial intelligence, and GPT4 bring multi-modal capability in dialogue system. It have potential to revolute whole finance system.

GPT series’ capabilities are mainly reflected in the following aspects:

- After performing Preprompt preprocessing, GPT can have a primary logical reasoning ability that meets requirements. Although this ability is unstable, when combined with frameworks like Wolfram, its reasoning and scientific computing capabilities will be greatly expanded.

- In dealing with unstructured natural language data problems, GPT has excellent analysis and restructuring abilities, enabling a vast amount of human data to be used. It can effectively transform multimodal data into structured semantics.

- When faced with multi-stage problems, GPT can effectively handle task scheduling and sequencing to help design an instruction architecture that meets system requirements. Many projects have begun to demonstrate their capabilities in this area.

For example:

AutoGPT:

https://github.com/Significant-Gravitas/Auto-GPT

Microsoft Jarvis:

https://github.com/microsoft/JARVIS

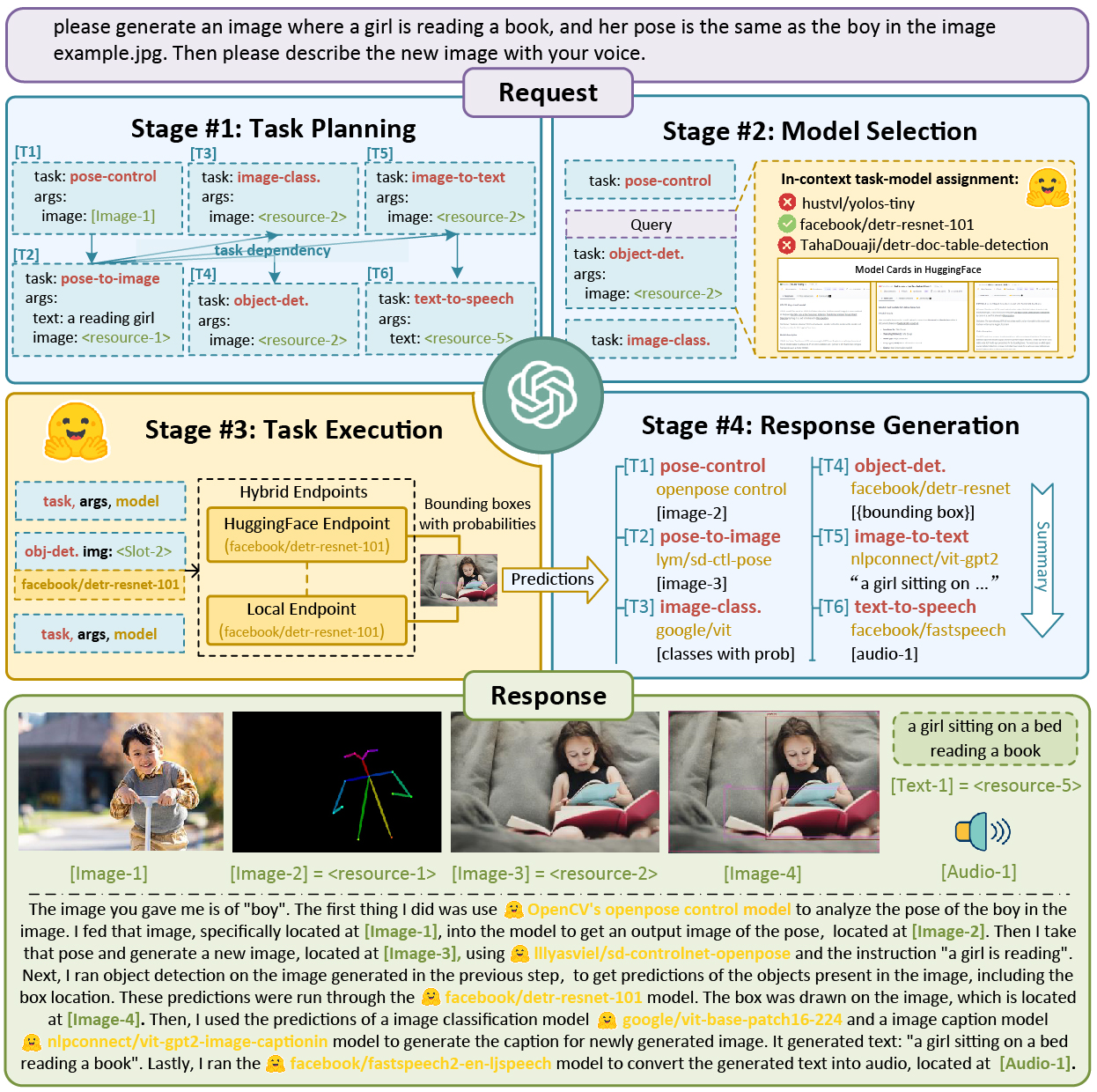

These two projects have extensively explored the potential of LLM Server as the core of a task system. For example, in the Jarvis project:

We introduce a collaborative system that consists of an LLM as the controller and numerous expert models as collaborative executors (from HuggingFace Hub). The workflow of our system consists of four stages:

- Task Planning: Using ChatGPT to analyze the requests of users to understand their intention, and disassemble them into possible solvable tasks.

- Model Selection: To solve the planned tasks, ChatGPT selects expert models hosted on Hugging Face based on their descriptions.

- Task Execution: Invokes and executes each selected model, and return the results to ChatGPT.

- Response Generation: Finally, using ChatGPT to integrate the prediction of all models, and generate responses.

Resources:

Reference:

- Andreas Fröhlich, Armin Biere, Christoph M. Wintersteiger, Youssef Hamadi: Stochastic Local Search for Satisfiability Modulo Theories . AAAI 2015.

- Nikolaj Bjørner and Anh-Dung Phan and Lars Fleckenstein. nu-Z: An Optimizing SMT Solver . TACAS April 2015.

- Nikolaj Bjørner and Arie Gurfinkel.Property Directed Polyhedral Abstraction. VMCAI 2015.

- Aleksandar Zeljic, Christoph M. Wintersteiger, and Philipp Rümmer. Approximations for Model Construction . IJCAR 2014.

- Markus N. Rabe, Christoph M. Wintersteiger, Hillel Kugler, Boyan Yordanov, and Youssef Hamadi. Symbolic Approximation of the Bounded Reachability Probability in Large Markov Chains . QEST 2014.

- Nikolaj Bjørner and Anh-Dung Phan. newZ: Maximal Satisfaction with Z3. Invited paper, in SCSS 2014 .

- Josh Berdine and Nikolaj Bjørner. Computing All Implied Equalities via SMT-based Partition Refinement. IJCAR 2014. Technical Report .

- Margus Veanes, Nikolaj Bjørner, Lev Nachmanson and Sergey Bereg.Monadic Decomposition. CAV 2014.

- Shachar Itzhaky, Nikolaj Bjørner, Thomas Reps, Mooly Sagiv, and Aditya Thakur.Property Directed Shape Analysis . CAV 2014.

- Nuno Lopes, Nikolaj Bjorner, Patrice Godefroid, Karthick Jayaraman, and George Varghese. *Checking beliefs in Dynamic Networks*. Technical Report. Revised version to appear in NSDI 2015.

- Thomas Ball, Nikolaj Bjørner, Aaron Gember, Shachar Itzhaky, Aleksandr Karbyshev, Mooly Sagiv, Michael Schapira and Asaf Valadarsky.VeriCon: Towards Verifying Controller Programs in Software-Defined Networks . PLDI 2014

- Nikolaj Bjørner, Konstantin Korovin, Arie Gurfinkel and Ori Lahav.Instantiations, Zippers and EPR Interpolation . Short paper at LPAR 19 .

- Josh Berdine, Nikolaj Bjørner, Samin Ishtiaq, Jael E. Kriener, Christoph Wintersteiger.Resourceful Reachability as HORN-LA . LPAR 19.

- Nikolaj Bjørner, Ken McMillan and Andrey Rybalchenko.Higher-order Program Verification as Satisfiability Modulo Theories with Algebraic Data-types . In informal proceedings of HOPA 2013 (workshop on Higher-Order Program Analysis).

- Nikolaj Bjørner, Ken McMillan and Andrey Rybalchenko.On Solving Universally Quantified Horn Clauses. SAS 2013

- Nikolaj Bjørner, Ken McMillan, Andrey Rybalchenko.Program Verification as Satisfiability Modulo Theories . SMT workshop 2012. Slides

- Nikolaj Bjørner, Vijay Ganesh, Raphael Michel, Margus Veanes. An SMT-liB Format for Sequences and Regular Expressions. SMT workshop 2012.

- Leonardo de Moura and Grant Passmore. Computation in real closed infinitesimal and transcendental extensions of the rationals. In Automated Deduction - CADE-24, 24th International Conference on Automated Deduction, Lake Placid, New York, June 9-14, 2013, Proceedings, 2013.

- Leonardo de Moura and Grant Passmore. The Strategy Challenge in SMT Solving, volume 7788 of Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence. Springer, 2013. [.pdf ]

- Leonardo de Moura and Dejan Jovanović. A model-constructing satisfiability calculus. In 14th International Conference on Verification, Model Checking, and Abstract Interpretation, VMCAI, Rome, Italy, 2013, 2013. [ .pdf ]

- Dejan Jovanović and Leonardo de Moura. Solving non-linear arithmetic. In Automated Reasoning - 6th International Joint Conference, IJCAR 2012, Manchester, UK, June 26-29, 2012. Proceedings, volume 7364 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 339-354. Springer, 2012. [ .pdf ]

- Dejan Jovanović and Leonardo de Moura. Solving non-linear arithmetic. Technical Report MSR-TR-2012-20, Microsoft Research, 2012. [ http ]

- Nikolaj Bjørner. Taking Satisfiability to the Next Level with Z3. IJCAR 2012.

- Anh-Dung Phan, Nikolaj Bjørner, David Monniaux. Anatomy of Alternating Quantifier Satisfiability. SMT workshop 2012. [ .pdf ]

- Krystof Hoder and Nikolaj Bjørner. Generalized Property Directed Reachability. In SAT 2012. [.pdf ]

- Christoph Wintersteiger, Youssef Hamadi, and Leonardo de Moura. Efficiently solving quantified bit-vector formulas. Formal Methods in System Design, 2012. [ http | .pdf ]

- Nikolaj Bjørner and Leonardo de Moura. Tractability and Modern Satisfiability Modulo Theories Solvers. In Handbook of Tractability. Cambridge University Press, 2012. [.pdf]

- Krystof Hoder, Nikolaj Bjørner, and Leonardo de Moura. muZ - an efficient engine for fixed points with constraints. In Computer Aided Verification - 23rd International Conference, CAV 2011, Snowbird, UT, USA, July 14-20, 2011. Proceedings, volume 6806 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 457-462, 2011. [.pdf ]

- Leonardo de Moura and Nikolaj Bjørner. Satisfiability modulo theories: introduction and applications. Commun. ACM, 54(9):69-77, 2011. [ http ]

- Dejan Jovanović and Leonardo de Moura. Cutting to the chase solving linear integer arithmetic. In Automated Deduction - CADE-23 - 23rd International Conference on Automated Deduction, Wroclaw, Poland, July 31 - August 5, 2011. Proceedings, volume 6803 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 338-353. Springer, 2011. [ .pdf ]

- Maria Paola Bonacina, Christopher Lynch, and Leonardo de Moura. On deciding satisfiability by theorem proving with speculative inferences. J. Autom. Reasoning, 47(2):161-189, 2011. [ .pdf ]

- Title: Natural language models and strategic command systems

- Author: Tom Winshare

- Created at: 2023-04-19 21:07:26

- Updated at: 2023-04-21 05:42:32

- Link: https://winshare.tech/2023/04/19/Natural language models and strategic command systems/

- License: This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.